Mold is the hidden menace lurking in the shadows of modern living, quietly wreaking havoc on human health. From damp basements to improperly ventilated offices, it infiltrates the spaces where we live, work, and breathe, releasing invisible toxins that silently assault the body. Yet despite its pervasive presence, mold remains a vastly underestimated and underdiagnosed driver of chronic inflammation and disease.

What makes mold especially insidious is its subtlety. Its symptoms often mimic other conditions—persistent fatigue, brain fog, respiratory problems, and unexplained aches—leaving many to search fruitlessly for answers. Meanwhile, mycotoxins, the harmful compounds produced by mold, ignite systemic inflammation, weakening the immune system and paving the way for autoimmune diseases, neurological disorders, and even cancer.

This isn’t just a problem of leaky homes or neglected basements; it’s an epidemic exacerbated by modern construction techniques, climate change, and a lack of public awareness. The mold epidemic is quietly undermining human health, yet it’s rarely discussed in the context of the chronic disease crisis. This article shines a spotlight on mold as a hidden driver of inflammation and disease, empowering you to recognize, address, and ultimately protect yourself from this stealthy invader.

The Chronic Biology of Mold: A Primer on Toxic Invaders

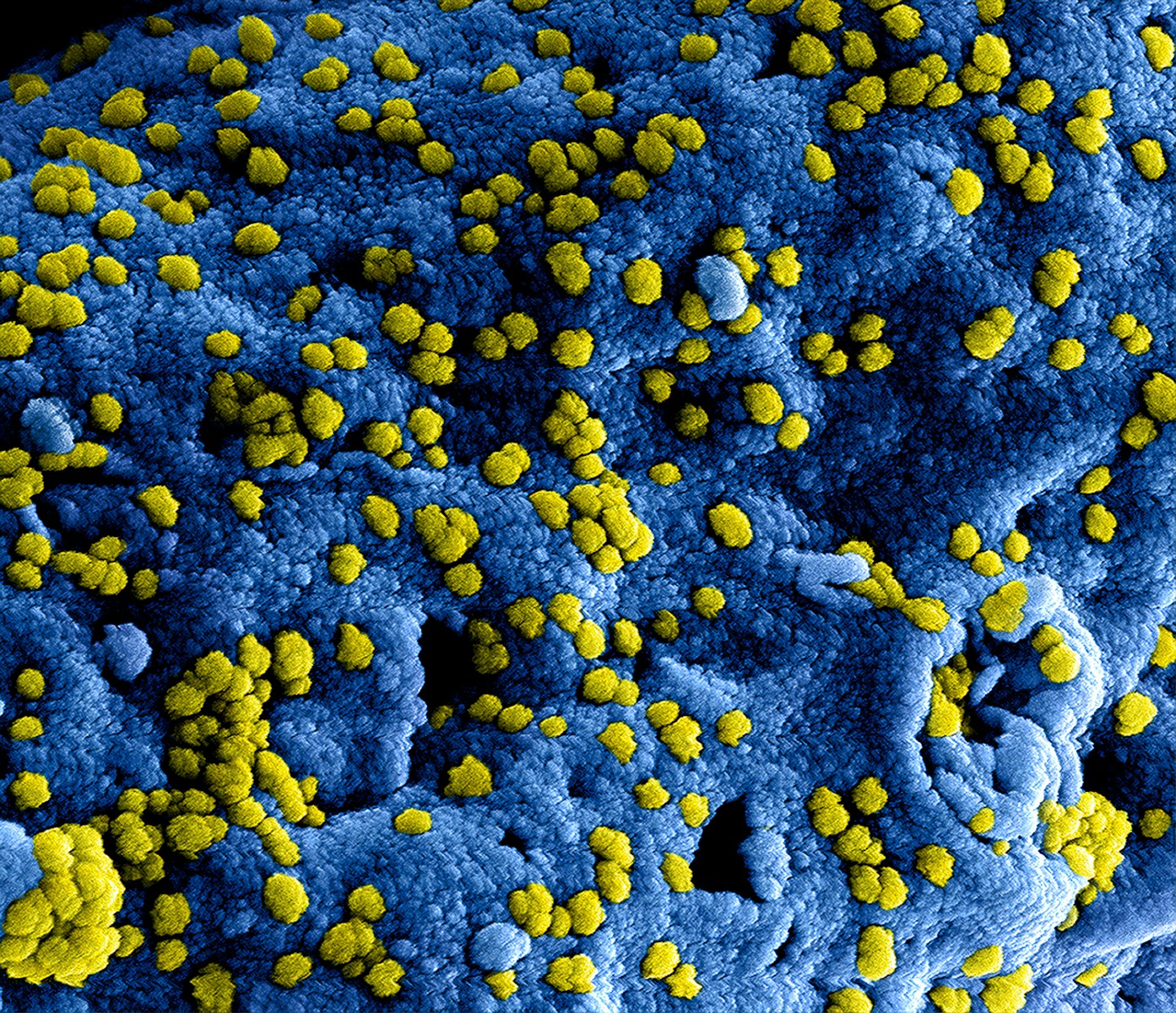

Mold is a type of fungus that thrives in damp, dark, and poorly ventilated environments. Its survival strategy is both simple and effective: it reproduces through spores, microscopic particles that drift through the air and settle wherever conditions are favorable. Once established, mold colonies can quickly expand, feeding on organic materials like wood, paper, and even the dust in your home.

What makes mold particularly dangerous isn’t just its ability to spread but the toxins it produces. Mycotoxins, the chemical byproducts of certain mold species, are highly toxic to humans and animals. These compounds are so small they can penetrate deep into the body when inhaled, ingested, or absorbed through the skin. Once inside, they act as stealthy saboteurs, triggering inflammation, disrupting cellular processes, and weakening the immune system.

Common molds like Aspergillus, Penicillium, and Stachybotrys (commonly known as black mold) are notorious for producing some of the most harmful mycotoxins. These substances can linger in the air and on surfaces, even after the visible mold is removed, prolonging exposure and amplifying health risks.

Mold isn’t limited to water-damaged homes or humid climates. It can hide behind walls, grow in HVAC systems, or contaminate food supplies. Modern construction techniques, which prioritize energy efficiency by sealing homes tightly, inadvertently create environments where moisture gets trapped, providing the perfect breeding ground for mold.

Understanding the biology of mold is crucial to recognizing its threat. It is not just an unsightly nuisance; it’s a toxic invader capable of profound harm. This knowledge sets the stage for exploring how mold exposure translates into a cascade of health issues that often go overlooked.

Chronic Health Consequences of Mold Exposure: Inflammation Unleashed

Mold exposure is far more than an inconvenience; it is a direct assault on the body’s inflammatory response system. The mycotoxins produced by mold are potent irritants that disrupt cellular function, overstimulate the immune system, and create a state of chronic, systemic inflammation. This inflammatory cascade is the linchpin in mold’s ability to wreak havoc on health, linking it to a range of debilitating conditions.

When mold spores or mycotoxins enter the body—whether through the air you breathe, the food you eat, or contact with your skin—they activate immune cells designed to combat perceived threats. These cells release cytokines, chemical messengers that amplify inflammation in an effort to neutralize the invader. In acute situations, this response is protective, but prolonged exposure to mold turns this defense mechanism against the body itself. The result is a state of low-grade, chronic inflammation that silently damages tissues and organs over time.

The symptoms of mold-related inflammation are as varied as they are insidious. Respiratory conditions like asthma and chronic sinusitis are among the most common, as the inflammatory response targets the airways. Neurological symptoms, including brain fog, memory loss, and mood disturbances, often stem from neuroinflammation—a direct effect of mycotoxins crossing the blood-brain barrier. Autoimmune diseases, already characterized by unchecked inflammation, can be triggered or worsened by mold exposure, as the immune system becomes overtaxed and begins attacking healthy tissues.

The gut is another major battleground. Mycotoxins disrupt the delicate balance of the gut microbiome, increasing intestinal permeability—commonly known as “leaky gut.” This allows toxins, undigested food particles, and even bacteria to enter the bloodstream, fueling further inflammation and creating a vicious cycle that underpins conditions like irritable bowel syndrome and systemic autoimmune disorders.

Perhaps most troubling is how mold-related inflammation compounds the effects of other health stressors. In a world already rife with processed foods, environmental toxins, and chronic stress, the inflammatory burden of mold can be the tipping point that drives the progression of chronic diseases like cardiovascular issues, metabolic syndrome, and even cancer.

Understanding the centrality of inflammation in mold-related illness is crucial. This is not merely about isolated symptoms or temporary discomfort; it’s about a deep, systemic process that undermines health at its core. Recognizing and addressing mold as a root cause of inflammation is the first step toward reclaiming well-being in the face of this hidden epidemic.

Mold in the Modern Environment: Why the Chronic Epidemic Is Getting Worse

The mold epidemic isn’t just a relic of forgotten basements or neglected homes—it’s a growing crisis exacerbated by the very design of modern living. Advances in construction, urban planning, and even climate shifts have unintentionally created a perfect storm for mold proliferation, making it an ever-present, yet often invisible, threat to health.

Modern building practices have prioritized energy efficiency over ventilation. Homes are now sealed tightly to reduce heating and cooling costs, but this also traps moisture inside. From condensation in windows to leaks that never fully dry, these conditions create the ideal breeding ground for mold. Synthetic building materials, such as drywall and composite wood, are particularly susceptible to moisture retention and mold growth, amplifying the problem further.

Climate change has also played a significant role in the mold epidemic. Rising global temperatures and increased humidity create environments where mold thrives year-round. Frequent storms, hurricanes, and floods have become more common, leaving water-damaged structures in their wake. Without proper remediation, these environments become mold hotspots, often impacting vulnerable populations in lower-income or disaster-prone areas the most.

Urbanization has added yet another layer to the problem. As cities expand, poorly maintained infrastructure—such as aging plumbing and leaking roofs—contributes to unchecked moisture buildup. Meanwhile, HVAC systems in office buildings and apartment complexes, if not properly cleaned and maintained, can harbor and distribute mold spores, spreading contamination through entire communities.

Food supplies are not immune to mold’s reach. Agricultural practices, storage conditions, and transportation systems are often inadequate to prevent mold contamination. Mycotoxins in grains, nuts, coffee, and dried fruits can accumulate, entering the human food chain undetected and contributing to systemic exposure.

Compounding this crisis is a lack of awareness and regulation. Building codes rarely address mold prevention, and public health policies often fail to acknowledge the scale of the problem. Many individuals and healthcare providers are unaware of the long-term health risks associated with chronic mold exposure, allowing the epidemic to grow unchecked.

The mold problem is no longer confined to damp basements and humid climates; it has infiltrated nearly every aspect of modern life. Understanding the environmental factors driving its proliferation is critical to addressing its health consequences. Until systemic changes are made in building practices, urban planning, and public awareness, mold will continue to thrive, quietly fueling inflammation and disease.

The Chronic Diagnostic Challenge: Identifying Mold-Related Illness

Mold-related illness is a master of disguise, masquerading as other conditions and eluding traditional medical diagnoses. The lack of standardized testing protocols and widespread knowledge among healthcare providers creates a diagnostic black hole, leaving patients trapped in a cycle of persistent symptoms without clear answers.

The symptoms of mold exposure are diverse and non-specific, ranging from chronic fatigue, brain fog, and joint pain to respiratory issues and skin problems. This symptom overlap with conditions like Lyme disease, fibromyalgia, and autoimmune disorders often results in misdiagnosis or dismissal of mold toxicity as a contributing factor. The root problem—chronic inflammation driven by mycotoxins—remains undetected, allowing the condition to worsen.

Conventional medical tests rarely screen for mold exposure. Routine bloodwork and imaging often come back normal, offering little insight into the body’s inflammatory burden. However, functional medicine and specialized diagnostics can provide valuable clues. Tests for elevated inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) or cytokines, can signal a systemic response, though they don’t pinpoint mold as the culprit. Advanced tests, like urinary mycotoxin analysis, can directly identify the presence of mold toxins, while nasal swabs and environmental testing can confirm exposure in a patient’s surroundings.

Neuroinflammation, a hallmark of mold-related illness, adds another layer of complexity. Brain imaging techniques, such as SPECT scans, can reveal patterns of reduced blood flow linked to inflammation, often correlating with cognitive symptoms like memory loss and difficulty concentrating. However, these findings must be interpreted alongside a patient’s history and environmental exposure to form a complete picture.

Another complicating factor is that not all individuals react to mold in the same way. Genetic predispositions, such as variations in the HLA-DR gene, make some people more susceptible to developing mold-related illness. For these individuals, the immune system struggles to clear mycotoxins, leading to prolonged exposure and heightened inflammation. This variability underscores the need for personalized diagnostic approaches.

The challenge isn’t only medical—it’s environmental. Identifying mold in a home or workplace often requires professional inspection and testing. Visual signs, such as black spots or a musty odor, are just the tip of the iceberg; hidden mold behind walls, in ventilation systems, or beneath flooring often goes unnoticed.

Diagnosing mold-related illness requires a paradigm shift in how we think about health. It demands a blend of clinical investigation, environmental testing, and patient-centered care. Until healthcare systems embrace the complexity of mold toxicity and its inflammatory consequences, millions will remain trapped in a cycle of misdiagnosis and untreated illness. Recognizing and addressing mold as a hidden driver of disease is the first step in breaking this cycle.

The Chronic Inflammatory Link: Mold as a Driver of Chronic Illness

At the heart of mold’s devastating health impact lies inflammation, the body’s natural response to injury or infection. While acute inflammation is a protective mechanism, chronic inflammation—triggered by ongoing mold exposure—becomes a destructive force, disrupting vital systems and driving the progression of disease. Understanding this inflammatory link is key to grasping why mold is such a potent catalyst for chronic illness.

Mycotoxins, the toxic chemicals produced by certain molds, are the primary culprits. When inhaled, ingested, or absorbed through the skin, these toxins provoke an immune response designed to neutralize the perceived threat. This response involves the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which signal immune cells to the site of exposure. In small, short-term doses, this is effective. But with repeated or prolonged mold exposure, the immune system becomes stuck in overdrive, flooding the body with inflammatory chemicals.

The cascade of inflammation doesn’t stay localized. It spreads through the bloodstream, creating systemic issues that affect nearly every organ. The respiratory system is one of the most immediate targets, with chronic sinusitis, asthma, and other airway conditions frequently linked to mold. But the damage extends far beyond the lungs. Mold-induced inflammation disrupts cellular function, increases oxidative stress, and weakens the body’s natural detoxification pathways.

The nervous system is particularly vulnerable. Mycotoxins can cross the blood-brain barrier, triggering neuroinflammation that leads to symptoms like brain fog, memory problems, and mood disorders. Over time, this inflammation contributes to neurodegenerative conditions, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. The gut, often referred to as the body’s second brain, is another critical area affected by mold. Inflammation here disrupts the microbiome, leading to leaky gut syndrome, food sensitivities, and a host of autoimmune disorders.

Mold also has a compounding effect on preexisting health conditions. For individuals already dealing with diabetes, heart disease, or autoimmune disorders, mold exposure exacerbates the inflammatory burden, accelerating disease progression and complicating treatment. Even seemingly healthy individuals can experience a breakdown in resilience over time, as the cumulative effects of low-grade inflammation erode their physical and mental well-being.

Chronic inflammation driven by mold exposure also interacts with other environmental and lifestyle factors, amplifying their impact. Poor diet, stress, and exposure to other toxins like heavy metals or air pollution can all magnify the inflammatory response, creating a perfect storm for disease development.

Mold’s ability to hijack the inflammatory response makes it a silent but powerful driver of chronic illness. To combat its effects, we must address not only the mold itself but also the underlying inflammation it perpetuates. This requires a multi-pronged approach that combines environmental remediation, dietary and lifestyle changes, and targeted medical interventions aimed at calming the immune system and restoring balance. Only by tackling the inflammatory link can we begin to dismantle mold’s insidious grip on health.

Solutions and Recovery: Fighting Back Against Mold and Chronic Inflammation

Confronting the mold epidemic requires a twofold strategy: eliminating exposure and addressing the damage it has already caused in the body. Mold is a resilient adversary, but with the right tools and approaches, recovery is possible. This journey begins with creating a safe environment and continues with targeted interventions to restore health and reduce inflammation.

The first step is to identify and eliminate mold exposure. Remediation of mold-infested spaces is non-negotiable. This often involves hiring professional mold inspectors who can detect hidden colonies in walls, HVAC systems, and other concealed areas. Visual signs or a musty odor are clues, but testing for airborne spores and mycotoxins is critical for a full assessment. Once identified, proper remediation involves not only removing visible mold but also addressing the underlying moisture problem—whether that’s repairing leaks, improving ventilation, or installing dehumidifiers.

For those recovering from mold exposure, air quality improvements are essential. High-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters can capture airborne spores and allergens, while activated carbon filters help trap mycotoxins. Regularly cleaning and maintaining HVAC systems prevents the recirculation of contaminants, creating a healthier indoor environment.

Detoxification is a cornerstone of recovery. The body needs support to eliminate mycotoxins and reduce the systemic inflammation they’ve caused. Binding agents, such as activated charcoal and cholestyramine, can help sequester toxins and carry them out of the body. These should be used under the guidance of a healthcare professional to avoid nutrient depletion or interference with other treatments. Hydration and a nutrient-dense diet rich in antioxidants are equally critical, as they bolster the body’s detox pathways and repair oxidative damage.

Diet plays a central role in calming inflammation and restoring gut health, often damaged by mold exposure. Avoiding inflammatory foods like sugar, processed items, and gluten, while emphasizing anti-inflammatory staples such as leafy greens, fatty fish, turmeric, and ginger, can help. Probiotics and fermented foods are key to restoring a healthy gut microbiome, which is often disrupted by mycotoxins.

Medical and functional medicine interventions may include addressing systemic inflammation through supplements like omega-3 fatty acids, curcumin, and N-acetylcysteine (NAC). Intravenous therapies, including vitamin C or glutathione, can provide additional detoxification support and reduce oxidative stress.

For those dealing with neurological symptoms, addressing neuroinflammation is critical. Therapies like transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), neurofeedback, and targeted nootropics may help repair cognitive function and restore mental clarity. Similarly, repairing sleep quality, which is often disrupted by inflammation, is essential for recovery. Melatonin, magnesium, and good sleep hygiene practices are effective tools in this effort.

Prevention is just as vital as remediation and recovery. Incorporating mold-resistant materials in construction and using mold inhibitors in high-moisture areas can prevent future growth. Regular home maintenance, such as fixing leaks promptly and controlling indoor humidity, ensures a mold-free environment.

The path to recovery from mold exposure isn’t quick or easy, but it is achievable with a comprehensive, proactive approach. By eliminating exposure, supporting the body’s detoxification systems, and reducing inflammation, individuals can break free from the grip of mold and regain their health. Mold may be resilient, but with persistence and the right strategies, so too are we.

Breaking the Silence on Mold

Mold is not just a household nuisance or a minor allergen—it is a pervasive, insidious force undermining human health and driving the chronic disease epidemic. Yet, its impact remains largely hidden, overshadowed by more visible environmental and health concerns. It is time to break the silence on mold and bring this issue to the forefront of public awareness, policy, and healthcare.

The first step in addressing the mold epidemic is education. People cannot protect themselves from a threat they do not understand. Schools, workplaces, and communities must be equipped with knowledge about mold’s dangers, how it thrives, and how to recognize its presence. Public health campaigns should elevate mold to the same level of concern as other environmental toxins, emphasizing its role as a driver of inflammation and chronic illness.

Regulatory action is also essential. Building codes and housing regulations must prioritize mold prevention, requiring proper ventilation, moisture control, and the use of mold-resistant materials in construction. Post-disaster recovery efforts, such as those following floods or hurricanes, should include mandatory mold inspections and remediation to protect vulnerable populations from long-term exposure.

The healthcare system must evolve to recognize and treat mold-related illnesses. This begins with training medical professionals to identify the subtle signs of mold toxicity and equipping them with the diagnostic tools necessary to confirm exposure. Insurance policies should cover mold testing and treatment, removing financial barriers that prevent many from seeking help. Research funding must be directed toward understanding the long-term health impacts of mold and developing innovative treatments for those affected.

At an individual level, every person has the power to act. Regularly inspecting homes and workplaces for signs of mold, addressing water damage promptly, and investing in tools like dehumidifiers and air purifiers can dramatically reduce exposure. For those already affected, seeking out mold-literate medical professionals and advocating for their own health is a vital step toward recovery.

Mold is a silent epidemic, but silence does not mean absence. It is time to speak up, to demand better policies, better healthcare, and better awareness. Mold thrives in darkness and neglect; shining a light on its impact is the only way to combat it. The mold epidemic may be a hidden crisis, but with knowledge, action, and determination, it can be confronted and overcome. The health of millions depends on it.